Measurement

of the railway.

In the railway, the rail is referenced by kilometrical

and heptametrical points (PK and PH).

These PKs refer typically to the axis of the

railway in case we work with a single railway, or to the axis of the gauge if

we have a double-railway.

But

we are especially interested in knowing the status of the outer rail of the

railway (driver rail). For this purpose we will measure and mark such rail,

where we will collect the data of the sagittas.

Marking of the outer rail

Starting

from a defined straight-alignment and a real known kilometric point

(hereinafter PKr), we will start drawing the head of the rail by its outer

side, from approximately 50m before the curve with a mark each 10m and up to

approximately 50m after the curve.

We

will number the points from “0” in the starting PKr, marking the “mark points”

(PKm): : the “1” to 10 m, the “2” to 20 m, etc. stressing the

marks each 50 and 100m in order to facilitate the double-check.

The

last point “n” will have a mark point (PKm) and a real mark (PKr).

The difference

between the PKr and the PKm of the measured point “n” will be known as “gap”.

Data of the references

All the references must be defined by a name (mast, wall, etc.), its PK and

its situation with regards to the railway (left (Dr)/ right(Iz)).

Once we have marked the curve we will define the longitudinal distance (L)

at which the points marked in the rail are placed and the perpendicular

distance to the closest rail (d).

In case of being working with a double-railway, we will also take as

references some distances to the gauge in front of the marked points.

Alignment of straight-lines

Starting from a defined point of a straight-line and placing the tachymeter

over the active face of the rail (or in a parallel to it), we will define the

definitive alignment of the straight-line, taking the data of the distance from

this alignment to the reference-points.

In the marking points (0), (1) and (2) as well as in the last points (n-2), (n-1) and (n) we will take the distance

existing from the alignment of the straight-line defined by the tachymeter and

the active face of the rail in those points, giving positive value if the

separation is placed between the straight-line and the center of the curve, and

negative value if it is placed oppositely.

We will call these distances: D0, D1, D2

y Dn-2, Dn-1, Dn

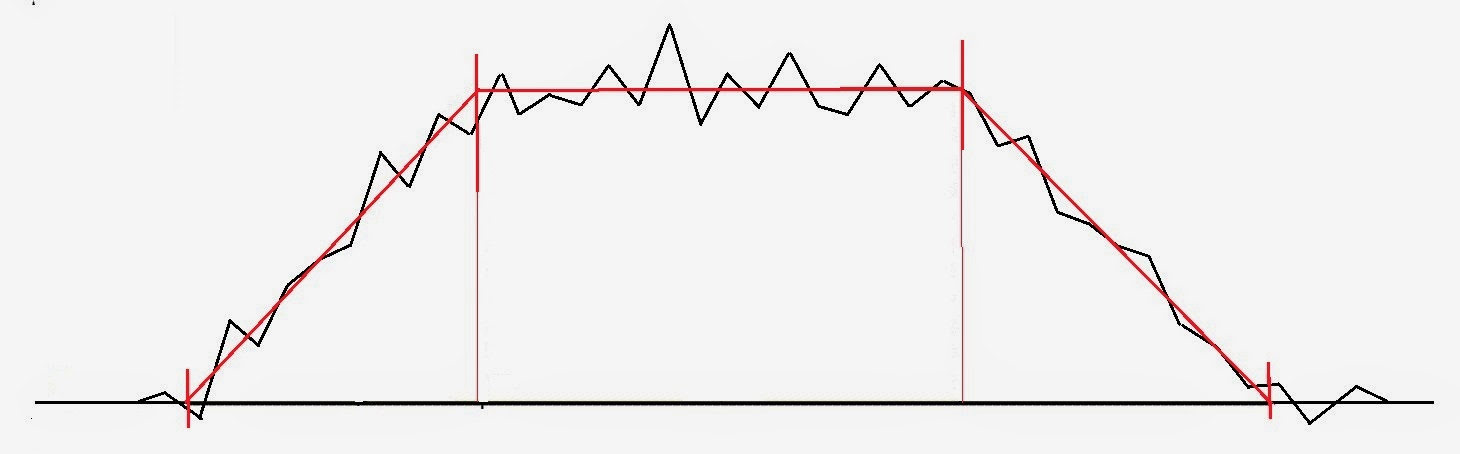

Sagittas of the curve

Using the “sagitta handles” (as those shown in the picture below), we will

place the first handle over the marking-point “0” and the second handle over

the point “2”, stretching out the nylon-chord perfectly (taking care of not

touching any obstacle), and we will measure the sagitta of the point “1”.

This kind of handles allow to separate the nylon 2cm from the active face

of the rail in order to measure negative sagittas, and therefore we must

subtract the 2cm to the measured sagitta.

Then we keep forward with the first handle to the point “1” and the second

handle to the point “3”, measuring the sagitta of the point “2”.

We will keep measuring until having the first handle over the point “n-2”

and the second over the point “n”, measuring the sagitta of the point “n-1”.

All the data collected will be

reflected in a document, similar to the one below:

Curve straightening

Before starting straightening a curve we must ensure that the curve is tangent to the straight-lines before and after it.For this purpose we will use the data collected in the line alignment (D0, D1, D2) and (Dn-2, Dn-1, Dn), as well as the sagittas taken in the points (1, 2) y (n-1, n).

The first Sagitta Law states:

F2= f2 + D2 - (D1/2)

- (D3/2)

Each “D” with its sign; “+” out, “-” in

A

corrected sagitta (F) is equal to

the measured sagitta (f) + (the

displacement in this point with the corresponding sign) – ( semi-displacement

of the point immediately before with the corresponding sign) - (semi-displacement

of the point immediately after with the corresponding sign).

- The sagitta in the point (0) is noted as (“0”): F0=0

- In the point (1) it will be : F1=f1 + D1- (D0/2) - (D2/2)

- The new sagitta in the point (2) will be: F2=f2 + D2 - (D1/2)

- The new sagitta in the point (3) will be: F3=f3 - (D2/2)

With this calculation we have created a line between the

points (0) and (2).

We will do the same in the exit line:- The new sagitta in the point (n-3) will be: Fn-3=fn-3-(Dn-2/2)

- In the point (n-2) it will be: Fn-2 = fn-2 + (Dn-2)- (Dn-1/2)

- In the point (n-1) it will be: Fn-1=fn-1+Dn-1- (Dn-2/2)-Dn/2

- And the sagitta in the point (n) will be noted as (“0”): Fn=0

Taking into account ALWAYS the sign of the displacements.

With this calculation we

have created a line between the points (n-2) and (n).

These new sagittas (F0, F1, F2) and (Fn-2,

Fn-1, Fn) will replace the sagittas really measured in

the document, writing as well the displacements (Do, D1) and

(Dn-1, Dn) in order to add them to the results of the

calculation.

So now we have all the

necessary data to straighten the curve:

- The curve is tangent to all adjacent lines

- We have measured all the sagittas of the curve

- We have placed all the references over with we will materialize the design

Now we will see some features of the curves and the sagittas.

If we increase the

displacements in a curve, then we will increase the sagitta or, which is the

same, we will reduce the radius. If we reduce the displacements, we will reduce

the sagitta or, which is the same, we will increase the radius.

The total angle of the curve (α) is always the same.

Its gravity center does not vary with one or other radius, as far as the entry and exit transitions remain the same.

The addition of the measured sagittas and the additions of the calculated sagittas, will be always the same regardless the radius.

The addition of the differences between the measured sagittas and the calculated sagittas will be 0.

GO TO CHAPTER VII - Alignment and Leveling of Railroad with Heavy Machinery

Full themes in the book -In paper and ebook (Follow the link)

------------------------------------------------

Medición de la vía.

En el ferrocarril la vía está referenciada por puntos kilométricos y hectométricos.

Estos PKs se refieren generalmente al eje de la vía en el caso de tratarse de una vía única o al eje de la entrevía en el caso de tratarse de vía doble.

A nosotros nos interesa conocer el estado del carril exterior de las curvas “carril director”. Para ello mediremos y marcaremos dicho carril, donde tomaremos los datos de las flechas.

Marcado del carril exterior

Partiendo de una alineación recta definida y de un punto kilométrico real (PKr) conocido, se comenzará a pintar en la cabeza del carril por el lado exterior, desde aproximadamente 50 m. antes de la curva con una marca cada 10 m. hasta aproximadamente 50 m. después de terminar la curva.

Numeraremos los puntos desde el punto “0” en el Pkr del comienzo, marcaremos los puntos de marcaje (PKm) : el “1” a 10 m, el “2” a 20 m, etc. Distinguiendo las marcas cada 50 y 100 ml, para facilitar la comprobación.Al último punto “n” le corresponderá un PK medida (PKm) y un PK real del trazado (PKr).

La diferencia entre el (PKr) y el (PKm) del punto medido “n” la llamamos desfase.

Todas las referencias las tenemos que definir por un nombre (poste, muro, etc.), su (PK), y su situación respecto a la vía (Dr/Iz)

Una vez marcada la curva definiremos a qué distancia en posición longitudinal (L) se encuentra de los puntos marcados en el carril y a qué distancia en perpendicular se encuentra el carril más próximo (d)

Caso de estar trabajando en un trayecto de doble vía, tomaremos también como referencias algunas distancias de entrevía frente a los puntos de marcaje.

Alineación de las rectas

Partiendo de un punto definido de una recta y situando el taquímetro sobre la cara activa del carril o en una paralela a este, definiremos la alineación definitiva de la recta, tomando datos de la distancia que existe de esta alineación a los puntos de referencia.

En los puntos de marcaje (0), (1) y (2) así como en los últimos puntos (n-2), (n-1) y (n) tomaremos la distancia que existe entre la alineación de la recta definida por el taquímetro y la cara activa del carril en esos puntos, dando valor positivo si esta separación está situada entre la recta y el centro de la curva o negativo si está situada en el otro sentido.

A estas distancias las llamaremos D0, D1, D2 y Dn, Dn-1, Dn-2

Flechado de la curva

Utilizando las “Asas de flechar”, colocaremos la primera “asa” sobre el punto de marcaje “0”, y la segunda “asa” sobre el punto “2”, extendiendo perfectamente el nylon que las une (teniendo cuidado de que no roce sobre ningún obstáculo), mediremos la flecha en el punto “1”.

Este tipo de asas, separan el nylon 2 cm de la cara activa del carril para poder medir las flechas negativas, por lo tanto a la flecha medida habrá que restarle esos 2 cm.

A continuación avanzamos la primera asa hasta el punto “1” y la segunda hasta el punto “3” midiendo la flecha en el punto “2”

Seguiremos hasta tener situada la primera asa sobre el punto “n” y la segunda sobre el punto “n-2”, donde mediremos la flecha del punto “n-1”.

Rectificación de curvas.

Antes de comenzar a rectificar la curva, debemos asegurarnos que la curva sea tangente a las rectas anterior y posterior.

Para ello utilizaremos los datos tomados en la alineación de las rectas (D0, D1, D2) y (Dn-2, Dn-1, Dn), así como las flechas tomadas en los puntos (1, 2) y (n-1, n).

La primera ley de las flechas dice:

F2=f2 + D2 - (D1/2) - (D3/2)

Cada “D” con su signo; “+” a exterior, “-” a interior

Una flecha corregida (F) es igual a la flecha medida (f) + (desplazamiento en ese punto con su signo) – (semidesplazamiento del punto anterior con su signo) - (semidesplazamiento del punto posterior con su signo)

- La flecha del punto (0) la anotamos como (0): F0=0

- En el punto (1) será : F1=f1 + D1- (D0/2) - (D2/2)

- La nueva flecha en el punto (2) será: F2=f2 + D2 - (D1/2)

- La nueva flecha en el punto (3) será: F3=f3 - (D2/2)

- La nueva flecha en el punto (n-3) será: Fn-3=fn-3-(Dn-2/2)

- En el punto (n-2) será: Fn-2=fn-2 + (Dn-2)- (Dn-1/2)

- En el punto (n-1) será: Fn-1=fn-1+Dn-1- (Dn-2/2)-Dn/2

- La flecha del punto (n) la anotamos como (0): Fn=0

Con este cálculo hemos creado una recta entre los puntos (n-2) y (n)

Estas nuevas flechas (F0, F1, F2) y (Fn-2, Fn-1, Fn) sustituirán en el impreso de medición a las flechas realmente medidas, anotando también los desplazamientos (Do, D1) y (Dn-1, Dn) para luego sumarlos a los resultantes del cálculo.

Ya tenemos todos los datos necesarios para poder rectificar la curva:

- La curva es tangente a las rectas adyacentes

- Hemos tomado todas las flechas de la curva

- Tenemos situadas las referencias sobre las que materializaremos el trazado.

- Si en una curva aumentamos los desplazamientos, aumentamos la flecha o lo que es lo mismo, disminuimos el radio, si disminuimos desplazamientos, disminuimos la flecha y aumentamos el radio.

- El ángulo total de la curva (α) es siempre el mismo.

- Su centro de gravedad no varía con uno u otro radio, si las transiciones de entrada y salida tienen el mismo valor.

- La suma de las flechas medidas y la suma de las flechas calculadas, será siempre la misma con cualquier radio.

IR A CAPÍTULO VII - Alineación y Nivelación de Vía con Máquina Pesada.

Temas completos en el libro - en papel y ebook (Siga este enlace)